Modern Yoga, Body Image, and the Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic

by Donna Gerrard

This paper was originally submitted as a 10,000 word dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA Traditions of Yoga and Meditation of SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies), University of London, 8th Sept 2021.

Abstract

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, as a yoga practitioner most of my life, and a yoga teacher over the age of 50 now with larger than average body size, I had been inspired by personal experience of body-shaming to explore the lived experience of body image in modern yoga. Modern Yoga has been subsumed into the modern health and beauty business, and as such it has become focused on the outward, physical results of the practices and beauty standards, which are rooted in systems of oppression. If modern yoga practice spaces are exclusively representing body images that reflect the projected norms of the dominant culture, then barriers are being presented to marginalized bodies. These bodies could most benefit from yoga practices to reduce stress and improve health and quality of life. The outbreak of the global coronavirus pandemic in 2020 and subsequent prolonged local ‘lockdowns’ have impacted the way that yoga is practiced globally. Using academic texts, survey data from modern yoga practitioners, non-academic and social media sources, this dissertation tests the hypotheses:

Practitioners of more active forms of Modern Postural Yoga such as Iyengar, Astanga and vinyasa are more likely to suffer body shaming microaggressions that those practicing Modern Meditational Yoga, restorative or yin practices;

Changes to ways of practice through the pandemic are beginning a step change which will change the embodied experiences of modern yoga practitioners for the better.

It explores modern yoga practitioners’ lived experience of body image prior to the pandemic, how this has been impacted by the global pandemic, and how both yoga and society must evolve to avoid the ‘othering’ of oppressed bodies.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge and thank all the wonderful lecturers at SOAS, particularly Ulrich Pagel and Graham Burns for their support, and Karen O’Brien-Kop and Sian Hawthorne, for their tremendous knowledge and inspiration in the fields of yoga and gender studies respectively. This dissertation was inspired by a presentation that I prepared for a discussion group with Karen. I am grateful for that experience as without it I would not have discovered the stellar human being who is Amber Karnes, who I thank for her teaching and endless inspiration. Thank you to all the 157 friends and strangers who gave their time and energy to share their stories and experiences so generously and vulnerably in my survey. Thank you to all my yoga teachers past and present, and friends and family, and particularly my partner, for their support. I must also say something about the other entity in this research, the coronavirus pandemic; thank you to all the healthworkers who continue to work so hard on behalf of us all in this challenging time.

Modern Yoga before the Coronavirus Pandemic

The term 'Modern Yoga' refers to certain types of yoga that evolved mainly through the interaction between Western individuals drawn towards Indian spirituality and certain Westernized Indians over the last 150 years. Most of Western yoga, and some contemporary Indian yoga, may be classified as Modern Yoga. The category is divided further into Modern Postural Yoga (MPY), which developed a stronger focus on the performance of asana (yogic postures) and pranayama (yogic breathing), and Modern Meditational Yoga (MMY), which relies primarily on concentration and meditation techniques. Typically, both MPY and MMY stress the orthoperformative side of participation within a classroom framework, extending to workshops and retreats for more committed practitioners. lyengar Yoga and Astanga Yoga are two relatively pure examples of MPY schools. MPY and MMY tend to limit themselves to very basic doctrinal suggestions concerning the religio-philosophical foundations of their practices. (De Michelis 2012: 2, 187)

.

Iyengar’s 1966 definitive text ‘Light on Yoga’ (LOY), with its precise, scientific approach to alignment and form revolutionized the way yoga is taught in the West (Cushman and Jones 1999: 221). Given the primacy of Iyengar in the DNA of MPY, perhaps recommendations in LOY of certain asanas ‘to reduce body weight’ (Iyengar 1966: 85) or ‘to reduce the size of the abdomen’ (ibid: 257) aided the subsuming of yoga into the health and beauty industry. Certainly Iyengar and his contemporaries followed the West’s example of branding their yoga offerings as a product to meet a marketplace need: in the case of Iyengar, that product was a mass-marketed postural yoga brand, representing fitness, modern biomechanics, and well-being (Jain 2014:94).

Despite the low profile of women in the early history of yoga, being deemed impure and subject to control and misogyny in the Vedic period and beyond (Bevilaqua 2017: 54; Törzsök 2014: 362), women now constitute around 80% of the global Modern Yoga community (Cartwright et al. 2020;Park et al. 2015:462). The ideals of modern postural yoga may even be said to include contemporary female ideals (Jain 2014:177). (Singleton (2010:160) even goes as far as to suggest that modern yoga has distinct ‘gendered yogas’.) Herein lies one of the many paradoxes of Modern Yoga. Five years ago, Miller (2016:2-3) opined that, at that time, the yoga industrial complex claimed that ‘yoga is for all bodies’, but that a typical Yoga Journal (YJ) magazine issue overrepresented what many claimed an unrealistic “ideal yoga body”. YJ images showed mostly White females, 3% or less images representing other races or anyone over the age of 55. 98% of bodies represented had nearly identical, slim measurements. The Yoga and Body Image Coalition (YBIC) was formed around that time to create awareness of access, inequality, exclusion; advocates of body positivity began using social media to drive systemic change.

Forty years after writing ‘Fat is a Feminist Issue’, Susie Orbach expressed how little progress Western society had made regarding body shaming:

‘We know how ubiquitous bad body feeling is. It is constantly stoked by visual images which invade us, by pronouncements disguised as health directives, by blandishments to do, be, brand, mark ourselves in ways that reward not the human body as a place we dwell in but as an object to enhance the profits of the beauty, fashion, diet, cosmetic surgery, food and exercise industries, no matter one’s age.[..] There is still a desperate search for approval, for safety, for body acceptance.’ Orbach (2018)

The yoga industrial complex is a micro representation of the macro: a curvy, black yoga teacher reflects that she always felt ‘different’ as a new yoga student, leaving the studio feeling ‘a vague sense of discrimination at the hands of my teachers and fellow students’ (Stanley 2017: viii). She is not alone: many students with bigger, disabled or non-conforming bodies have faced hostilities in fitness environments like gyms and yoga studios (Karnes 2017). Other prominent curvy yoga teachers have written of students leaving a class upon learning they are the teacher (Bondy 2014; Guest-Jelley 2012).

Why is this sense of ‘Othering’, or lack of representation, important? Power is internalized and exercised by the dominated subjects themselves, in a format that bears the seductive mark of consumer culture (Foucault quoted in Askaard and Eckhardt 2012: 54). Members of both the patriarchal culture and the yoga community have internalised the ideals of the culture and are applying it in the yoga milieu, creating stereotypes regarding who is a yogi, how a yogi looks and moves, and what defines yoga (Hall 1997: 259). Representation models which bodies are more yogic; Others are not. Bodily representations create boundaries between ‘yogi’ and ‘Other’ (Miller 2016: 7- 8).

Why though should we be so concerned about this ‘Othering’? Miller (2016:8) steers us towards the key issue, recounting the experiences of a curvy yogi who expresses that of all the sports and athletics she had participated in as a fat person, the yoga space was sadly one of the most judgmental and the least emotionally safe. She goes on to describe numerous ways that both students and teachers contribute to making curvy yogis uncomfortable in their classes, whether that be in unsolicited recommendations of fitness or weightloss programs, assuming they are new to yoga or in some way ‘disabled’, or adjusting in unsafe ways for larger bodies. These ‘microaggressions’ are displays of oppression. Oppression is learnt through the daily lived experience of social and political life, and oppression is traumatic (Johnson 2017: 4,5). An environment has been created within Modern Yoga that marginalizes and traumatises Othered yogis, especially those in fat bodies. Modern Yoga has to do better than this.

The Coronavirus Pandemic

World Health Authority declared coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a pandemic on 11 March 2020. To prevent spread and provide sufficient time for hospitals’ readiness in their respective countries, worldwide governments imposed ‘lockdown’. Under lockdown, people are restricted to remaining indoors, with only certain permitted local exceptions (Nagarathna et al. 2021:2). In the UK, for example, on 23 March 2020, UK residents were ordered to stay at home (Source: Institute for Government analysis, Timeline of UK coronavirus lockdowns, March 2020 to March 2021). Public venues such as yoga studios were obliged to close. Annie Rice expresses the typical impact on yoga teachers (most of whom are self-employed), and by extension their students, in the UK:

‘When the pandemic hit, I, like most self-employed yoga teachers, panicked for a week and then quickly constructed a new working life via Instagram live classes, eventually finding a Zoom rhythm that would pay the rent.’ Rice (2021)

Rice describes the move to online teaching platforms that resulted from the global lockdowns, in an attempt for teachers and studios to retain some income and to sustain relationships and service to their students. Social media such as YouTube, Instagram TV and Facebook Live became popular ways for teachers to broadcast online classes (Sharma et al. 2020:1), albeit without interaction between teacher and student. The Zoom application was widely adopted as a popular platform to offer interactive video classes. Zoom offers the possibility for participants to congregate in an online group environment, with individual participants able to choose whether to switch their own cameras on or off; participants have personal agency and choice around whether they are seen by other participants. Teachers were managing to find an alternate way to continue to connect with their students despite the social distancing and lockdown, although many were missing the in-person experience of a yoga class. It was possible however that perhaps this shift online could have a remediating effect on the marginalisation and resulting traumatisation of Othered yogis. I was keen to explore this further.

The Study

In order to learn about modern yoga practitioners’ experience of body-shaming and lack of inclusivity in yoga, and if changes to methods of practice during the coronavirus pandemic were shifting this in any way, an internet survey was designed and shared to my email and social media contacts. Data was gathered from July 2020, when UK was in lockdown, to October 2020, when UK lockdown had been eased somewhat but then reintroduced (Timeline of UK coronavirus lockdowns). For reason of cost of implementing the survey, questions were phrased as long and open.

Responses were spell checked and manually extracted from the response text into the various data fields for analysis, removing and discarding full names and contact details, leaving only first name where permission had been given for this to be shared. Heights and weights were all converted to metric measurements, BMI calculated (Method used: CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) BMI Calculator) and the underweight/ normal/ overweight/ obese classification recorded, as means to group and classify respondents.

Unfortunately the disadvantage of having implemented the questionnaire in the form of free text responses meant that some respondents did not provide all the data points. Meaningful analysis was still possible though; for example, 46% of respondents did not provide an explicit answer to the question ‘Do you think that teaching and practicing yoga online makes the kinds of experiences described in question 8 more or less likely?’ The answers provided by 72 respondents still enabled conclusions to be drawn.

A note about the use of BMI

There are both detractors and proponents of BMI. Like any other Western medical measure, it is imperfect. It can however provide both a common language (albeit perhaps that of ‘the oppressor’), and valuable insights into individual and social condition when framed as a holistic assessment of health relative to weight (Gutin 2018:9; Hedva 2016:6). I am purely using it as a means to classify height to weight ratios, without relative health judgement, to indicate how bodies may be ‘seen’ and hence how they may be judged and othered.

Study Summary

Context:

Pre-coronavirus pandemic, Modern Yoga had been subsumed into the health and beauty industry, which is motivated by patriarchal and capitalist values, and was causing harm through body shaming microaggressions.

Hypotheses:

Practitioners of more active forms of MPY such as Iyengar, Astanga and vinyasa are more likely to suffer body shaming microaggressions that those practicing MMY, restorative or yin practices.

Changes to ways of practice through the pandemic are beginning a step change which will change the embodied experiences of modern yoga practitioners for the better.

Study Purpose:

To gather data around the topic of body image in modern yoga, enabling better understanding of the embodied experience of modern yoga practitioners.

To also understand how practice styles are changing with the coronavirus pandemic, how this is impacting practitioners’ embodied experience, and their opinions on whether these changes could have lasting positive impact.

Number of subjects:

Targeted: 50-100 responses.

Received: 157

Age: 18 upwards, no upper limit.

Gender: All

Location: Global

Dates of study: July - October 2020

Inclusion criteria:

Yoga practitioners

Age 18+

English speakers

Exclusion criteria:

Non-yoga practitioners

Non-English speakers

Withdrawals/ drop-outs:

Respondents were given the choice to include their anecdotal evidence in the data analysis only, or to give permission to be quoted explicitly in the report, and if so whether permission was given to use their name.

I have only used first names where permission was given.

Measures used: ‘Survey Monkey’ Online Questionnaire

Survey questions

1. Please detail your demographics: (Age, Sex, Height, Weight, Country and Region of residence, Racial group (optional), Sexuality (optional)).

PLEASE BE ASSURED THAT THIS DATA WILL BE HELD COMPLETELY CONFIDENTIALLY, WILL ONLY BE USED FOR DATA ANALYSIS, AND ONLY SHARED WITH YOUR EXPLICIT PERMISSION .

2. How long have you been practicing yoga?

3. What style(s) of yoga do you practice (e.g. hatha yoga, Iyengar, yin, Hot/Bikram, vinyasa, restorative)? Please list all.

4. What types of yoga practices are included in your yoga practice (e.g. asana (postures), pranayama (breathwork), mudra (hand gestures), mantra (chanting), meditation). Please list all.

5. What drew you to yoga initially?

6. What keeps you practicing?

7. Where do you generally practice (e.g. home, studio, community centre)?

8. During your history of practice, can you describe any negative experience(s) you may have had: physical/verbal/sexual abuse, any experiences of classes or teachers who made you feel in some way 'less than', e.g. too old, too large, or in some way not 'a fit'? If so, how did you act in response?

9. What are your observations of how (if at all) the practice of yoga is changing with the pandemic? Do you think that teaching and practising yoga online makes the kinds of experiences described in question 8 more or less likely?

10. Please add your name (only if you wish) and whether you give permission for me to share any anecdotes you have given in your answers in my dissertation writeup, and whether you give permission for this to be shared with your name or as an anonymous responder.

Survey Results

Graphs were plotted (figures 1 to 7) showing the geographical and gender distribution of respondents, length of time practicing yoga, practice styles, yoga practices engaged in, what attracted them to yoga initially, and what keeps them practicing.

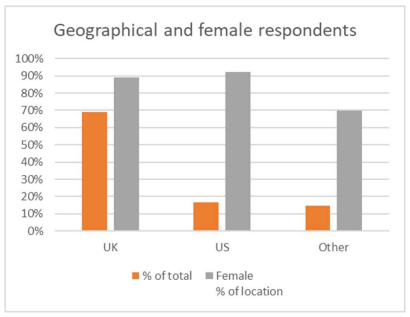

The 157 respondents represented over 2,000 years’ yoga practice in total. Respondents primarily came from UK (69%), with 17% from North America, 7% from the rest of the world; 6% did not provide a location. Female identifying respondents represented 89% from the UK, and 92% from the US. The UK figure is closely representative of the 87% of yoga practitioners in the UK who are female. (Less so for the equivalent US figure of 76%.) (Cartwright et al. 2020; Park et al. 2015:462). I have analysed the data set as a whole, ignoring local variations, with the assumption that all are relevant to the topic of Modern Yoga and the context of the global pandemic.

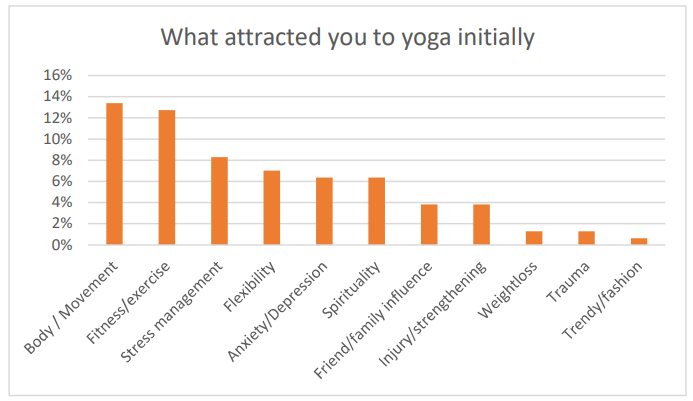

Evidence indicated that many were drawn to yoga initially for reasons of fitness or physical body ‘improvement’, but most are drawn back to practice habitually having experienced the less physical benefits of peace, wellbeing and mental hygiene.

Having plotted this contextual data, I began to analyse body shaming data in more detail. On the subject of inappropriate touch, 7% of respondents described incidents from yoga teachers, either sexually inappropriate or physical assists that were unwanted, inappropriate or caused injury, within the subset of vinyasa, Iyengar, Astanga and Jivamukti practitioners. Much as this subject is relevant to the overall discussion of how the practice of yoga needs to shift, this specific area is out of the scope of any further analysis for this dissertation.

Figure 1: Gender and geographical location of respondents

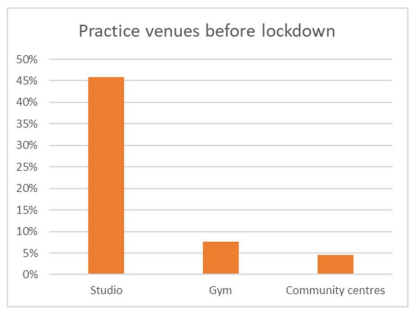

Figure 2: Typical yoga practice venues before lockdown

Figure 3: Distribution of number of years of yoga practice of respondents

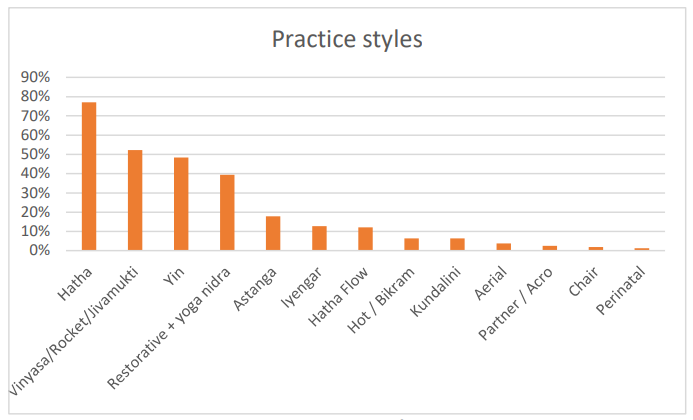

Figure 4: Practice styles of respondents

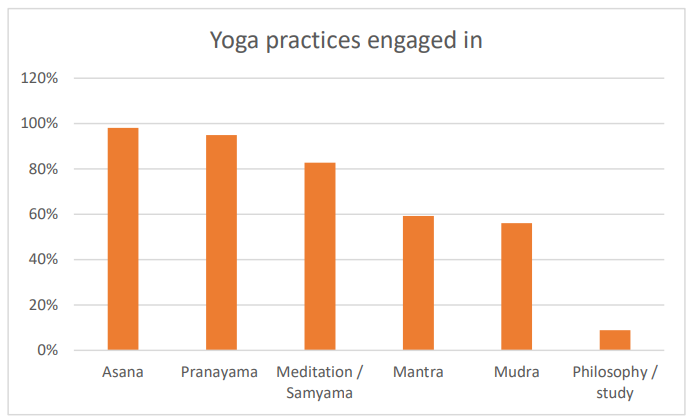

Figure 5: Yoga practices engaged in by respondents

Figure 6: What attracted respondents to yoga initially

Figure 7: What keeps respondents practicing

Experiences of body shaming

What became clear as I analysed the data responses was that body shaming experiences fell into two categories:

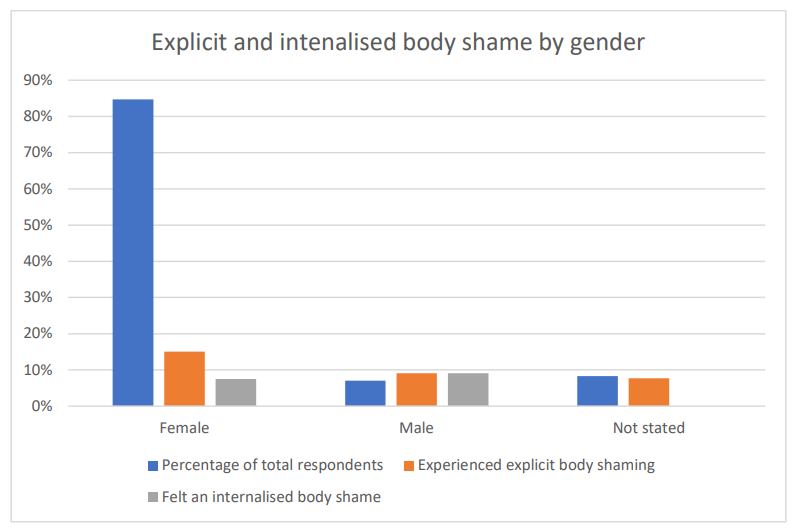

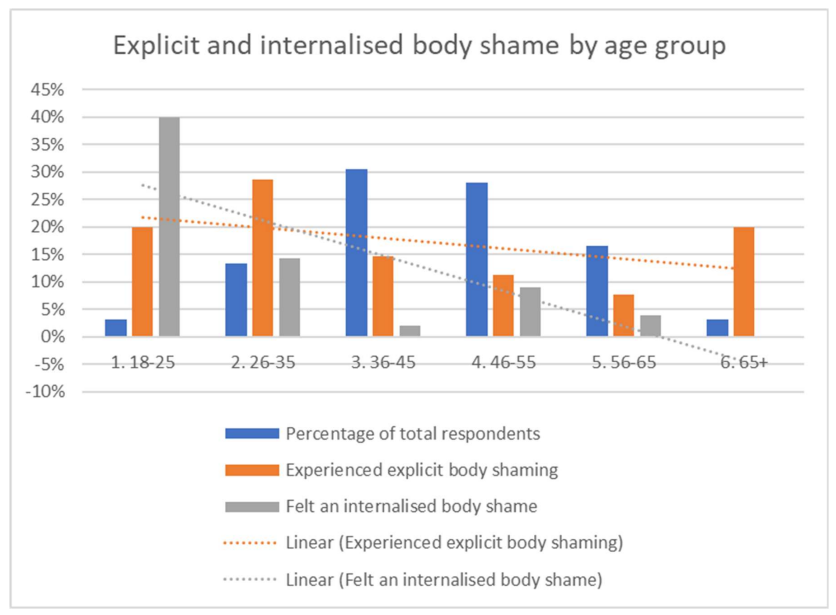

Respondent had received verbal or behavioural microaggressions from teachers, studio staff or fellow students (14% of all respondents).

Respondent had expressed an internalised ‘a felt sense’ (Gendlin 1982:10) of their body being Othered for the practice, even if this had not been instigated explicitly by another party’s behaviour (7% of all respondents).

Figures 8, 9 and 10 plot the distribution of explicit and internalised body shame by gender, and by BMI irrespective of gender, and by age, respectively. Both explicit and internalised body shame both show an upward trend with BMI. Interestingly, explicit body shaming by age group shows a very slight downwards trend by age, but internalised body shame shows a very strong downward trend with increasing age group: yoga practitioners would tend to be more accepting of their own bodies as they age.

The anecdotal reports from larger bodied practitioners about their experiences of body shaming make for unpleasant reading, and range from feeling uncomfortable in studios, feeling ‘too big’ for the practice, disapproving facial expressions, being called out for being ‘slow’, rejected for yoga teaching jobs because of body size, to physical abuse for size (Appendix 1).

Body shaming experiences are not limited to those in large bodies. Slimmer bodied practitioners cited being called out for being ‘skinny’ in classes without awareness that this could be triggering, or that the student could be recovering from an eating disorder (Appendix 2). One 40 year old female teacher with a normal BMI gave a sorry indictment of the views of some yoga clothes brands, saying that a clothing label had declined her representing their brand because she is ‘too old and too round to fit into their clothes.’

Figure 8: Explicit and internalised body shame by gender

Figure 9: Explicit and internalised body shame by BMI classification

Figure 10: Explicit and internalised body shame by age group

Hypothesis 1: Practitioners of more active forms of MPY such as Iyengar, Astanga and vinyasa are more likely to suffer body shaming microaggressions that those practicing MMY, restorative or yin practices.

I was also interested to determine if there was any connection between body shaming and the type of yoga practice, to test the hypothesis that practitioners of more active forms of MPY such as Iyengar, Astanga and vinyasa are more likely to suffer body shaming microaggressions than those practicing MMY, restorative or yin practices.

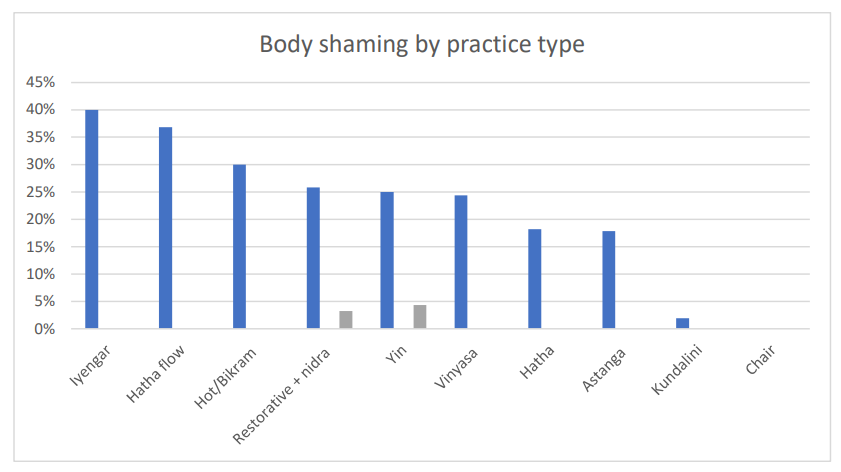

Practitioners of all ‘active’ type practices (i.e. excluding restorative, yin and chair yoga) except kundalini reported experience of body shaming rates between 18% and 40% of the total number of practitioners engaging in that style (Figure 11).

Data points that were initially surprising were that 26% of restorative and 25% of yin yoga practitioners had reported body shaming. However, refining these samples to exclude those also engaging in more active styles, reduced the incidents significantly, to 3% and 4% respectively (represented by the grey bars on the chart), thus proving hypothesis 1 of the study.

Figure 11: Distribution of body-shaming reports across types of yoga practice.

(Grey bars are adjusted to remove numbers of active-type MPY practitioners from those subsets.)

Pandemic Yoga Practice

With all yoga practice limited to home as described by Rice (2021), respondents reflected on their experiences of finding space in their homes to practice, with teachers interacting via Zoom, or recording their classes for broadcast by their studios. Respondent Firdose observed that a sizeable number of people took up yoga for the first time during the pandemic, meaning that perhaps beginners felt less intimated to start the practice from the comfort of their own homes.

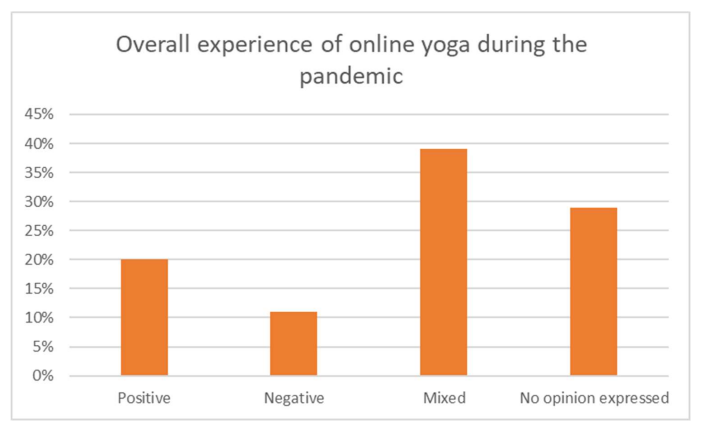

Figure 12: Overall experience expressed of practicing yoga online during the pandemic

Exclusively positive experiences of online practice were expressed by 20% of respondents (‘I've had some great online classes’), many citing the benefit of wider locational reach:

‘practicing online has made yoga accessible to so many more people. It has [..] given us the opportunity to practice with so many great teachers from around the world’.

A key theme reported by proponents of practicing online is that there is ‘less nastiness’ regarding weight and ability. Greater personal agency and choice is offered by online practice; practitioners report being able to modify their practice to suit their own needs, or to take a break, without feeling that they are distracting the class. Others observe many being comfortable in the anonymity offered by switching Zoom cameras off:

‘People who might be embarrassed to go to a physical class can do them at home and might not feel so noticeable or different. ‘

There is also the potential for greater authenticity of practice, moving away from external images towards the internal experience:

‘Virtual yoga sessions have made the practice more internal and more about personal experience than what others see of you.’- Winnie

‘[It’s] good for people to focus on themselves in isolation and not have to think about the image they portray. Nobody cares online if you have a Lifeforme mat, flat abs and matching Lululemon outfit. Hopefully it can become a more authentic practice, back to its roots.’

‘since many leave their camera off, I instruct them to listen to their bodies and do what feels right.’ - Nikole

Respondent Amanda feels ‘safer and more relaxed practicing and teaching in the comfort of my own home’, which is important in the context of creating safer spaces for the practice.

Solely negative experiences of online practice were reported by 11% of respondents, citing lack of personal connection, group energy, and sense of community, from perspective of both teachers and students. There are also concerns expressed around the limited ‘emotional support to deal with whatever is released through the practice’ without an instructor in the room, and safety, given the limited view by the teacher, even if students keep their cameras on. As lockdown progressed, some yoga teachers were reporting that classes were reducing because ‘people are fed up with screens’, or ‘Zoomed out’ (Weber 2021a).

There are those who are not able to experience ‘screen fatigue’, as accessibility to the internet is a prerequisite for online yoga practice, whether through streaming or Zoom:

‘the only people that can practice during lockdown are those with high-speed internet connections and space, so that adds a different dynamic.’ - Firdose

An anonymous teacher respondent in the Scottish Borders explained that she had not been able to move to teach online due to poor internet connection in her locality, and their older students generally having neither computers or internet access. This highlights that ability to practice online has a level of privilege.

The majority of respondents (39%) described a mixed positive and negative experience of online practice during the pandemic, with many enjoying the ability to practice around their families and work lives, but missing the class dynamics and the benefits of in person teaching; ‘It is both more and less intimate than teaching in real life.’ (Rice 2021)

The impact of online teaching on abuse and body shaming

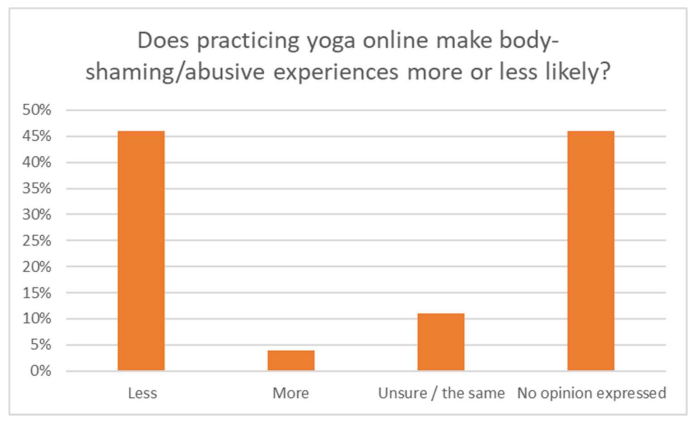

Figure 13: Did respondents think practicing yoga online made body-shaming experiences more or less likely?

Hypothesis 2: Changes to ways of practice through the pandemic are beginning a step change which will change the embodied experiences of modern yoga practitioners for the better

Nearly half (46%) of the respondents anticipated that online teaching would make the opportunity for abusive behaviour, such as body shaming, less likely. At a superficial level therefore hypothesis 2 of the study is proven.

An equal number expressed no explicit opinion in their answers. 11% were unsure, or expressed that practicing yoga online did not change the likelihood of abusive behaviour.

Only 4% of respondents answered that they thought that teaching and practicing yoga online made body-shaming/abusive experiences more likely. Three responses call for further examination:

‘People can still be mean on Zoom and make comments that everyone hears. But at least you're in the comfort of your own space. No shaming eyes looking at your belly.’

This individual has experienced microaggression over a live internet call, which must be very distressing. She suggests previous experience of shaming looks at her stomach also. The shame she feels is symptomatic of the targeting of soft and ‘excess’ body weight deemed unacceptable under capitalism, reflecting moral or personal inadequacy. Significantly, the part of the anatomy most frequently targeted for vicious attack, and most despised by the inhabitant of the body, is the stomach, the symbol of consumption (Bordo, 1993).

This unkind sentiment is echoed by the first of two other respondents, who expressed concern about the influence of social media on online yoga practices:

‘I think the "Instagram Generation" style of yoga has sadly become more about how good the picture is/how perfect the person looks not what yoga is actually about. Yoga is for everybody but that's not reflected on social media and with us all being online a lot more at the moment, I think many people will be put off trying yoga. Unfortunately, people are braver about saying mean things on social media than in real life because it's almost anonymous, so I wouldn't be surprised if the problem had got worse this year.’

‘I am worried that teaching online will exacerbate the focus on the asana and what a body "should look like" in poses - I teach online and students have said that their are frustrated their body does not "look" as flexible or the way mine does in certain poses, and I've witnessed some self shaming from the students that their body doesn't "work" in those ways. I am concerned that the subtle practice of yoga is being lost amidst the focus on flexibility and glorification of the performative asana of size 8 body types.’

This respondent refers to the subtlety of yoga being lost in the brash world of social media. Social media is full of contrasts; comforting and distracting and yet sneaky (brown (sic.) 2017:207). YBIC was formed to create awareness of access, inequality and exclusion, and social media is often the platform over which members advocate for body positivity (Miller 2016:2-3).

How is social media both helping and hindering the reduction of body shaming behaviour? This respondent feels that social media is showing a wider, more inclusive view of yoga bodies than in the past:

‘I think in the earlier days of practice, there was definitely a stigma to attending classes if you weren't a certain build. I think that with social media it is much more open now to people of all ages, shapes and size. I have never stopped doing yoga because of how I look, but maybe I felt self consciousness sometimes.’

A yoga teacher trainee and a teacher, however, are of the opinion that social media images are continuing to reinforce yoga body stereotypes:

‘We have to submit pictures of asanas to be looked at for yoga teacher training. I feel very nervous being exposed like that for people to critique. I think Instagram and social media have done more harm to body image of yogis than anything.’

‘I think the "Instagram Generation" style of yoga has sadly become more about how good the picture is/how perfect the person looks not what yoga is actually about. Yoga is for everybody but that's not reflected on social media.’

This teacher goes on to observe that because of the relative anonymity, many, unfortunately, are braver to make unkind remarks on social media than in real life, and so would be unsurprised if the problem of microaggressions had worsened under lockdown. The reality of post-pandemic yoga is likely to be more nuanced than this survey datum point implies. I conclude this section with this articulate summary by one respondent:

‘As a student [online] you're less likely to be touched inappropriately or called out by a teacher, and you also have the option to turn off your own video feed if you wish to, so these instances [of abuse] may currently be less likely to happen.

The only thing that will change behaviour within those [in person] spaces is if teachers in training are put through mandatory and in-depth subconscious bias/anti-discrimination training and more people from minority backgrounds can afford to become teachers in the future.’

The statement leads me to the conclusion that online yoga is the more beneficial with regards to reduction of microaggressions.

Intersectionality

The impact of unrealistic body standards is intersectional (Crenshaw 1991), meaning that various dimensions of identity such as gender, race, class, ability, sexual orientation, or body size, interact on multiple and often simultaneous levels to produce complex systems of oppression or discrimination (Miller 2016:10). Our experiences are shaped by multiple and intersecting social identities (Johnson 2017). This was borne out by the lived experience of many of the survey respondents.

Natalie and Lee related stories of being or feeling shamed for the combination of body size and ability:

‘[I experienced] assumptions made because of my weight and being a yoga teacher. More often the surprise of “Wow you can do that even though you're fat”.’ - Natalie

‘A teacher made me feel bad for not having stronger wrists and did nothing to help me. I was the largest in the class and I felt excluded though she did not actually say so.’ - Lee

Rosie reported experiences of a condescending combination of ageism, fat shaming and ableism:

‘I was 5 stone heavier until 4 years ago. [..] Worst thing was sometimes being patronised. “You do awfully well considering your age/weight/bad knees” etc.’ - Rosie

Body size, ability and economic accessibility were referenced by one anonymous respondent, who described that online yoga during the pandemic is more accessible to them, as they have trouble getting out independently. They acknowledged a greater availability of practices, but that price was often still prohibitive.

The combination of racism and fat shaming was cited by 3 respondents; one of these, Amrita, related feeling constantly othered as a plus size Indian Yoga teacher, reacting by leaving the studio every time.

Two respondents’ stories in particular inspired my curiosity about whether the voices of these unique and diverse experiences of complex oppression, at the intersection of multiple identities, could tell more about how the landscape of post-pandemic yoga may look.

Case Study 1: Gill

This is the story of Gill, a larger bodied fibromyalgia sufferer:

Question 8: During your history of practice, can you describe any negative experience(s) you may have had: physical/verbal/sexual abuse, any experiences of classes or teachers who made you feel in some way 'less than', e.g. too old, too large, or in some way not 'a fit'? If so, how did you act in response?

‘When I first started practicing, I went to an all levels class but the teacher clearly only wanted to teach advanced practitioners. She started shouting at me 'green leggings you are a liability!' And really shamed me. All I had done was lifted my shoulders slightly off the floor in a reclined leg stretch. I was so humiliated I didn't go back to yoga for two years. On my teacher training I opted not to assist someone in a handstand because I had extremely painful knees that day (fibromyalgia) and didn't trust that I could be a stable base for my partner. My teacher yelled at me 'Did you come here to sit and watch or did you come here to learn?’ That same teacher mansplained periods which was terrible/funny. I've been told numerous times by teachers ridiculously lines such as 'If I can do it you can do it'. As if not being able to do an asana related to me being lazy and not to the fact that I have an invisible illness. When I tried to apply for a particular training the teacher in charge brushed me off and gave me a fake name of who to apply to because she only really wanted bendy teachers on her course. I brushed it off and did the course anyway and felt totally alienated throughout. I've been adjusted in ways that didn't feel quite right by male teachers. A teacher told me that I couldn't do a particular bind because 'you have karma in your svadhistana chakra' He basically meant I have a tummy but was too smart to say it outright. It's a wonder that I kept practicing to be honest but somehow I understood that yoga was in its essence powerful beyond all the bullshit. I wanted to become a teacher to offer a different experience to people.’

Question 9: What are your observations of how (if at all) the practice of yoga is changing with the pandemic? Do you think that teaching and practising yoga online makes the kinds of experiences described in question 8 more or less likely?

‘It rules out inappropriate adjustment and lessens the opportunity for teachers to judge your practice by your outward mobility. I think we can still experience body shaming via Zoom. I think Zoom opens up the possibility for more accessible practices too. But it misses that magic of collective energy.’

Gill has experienced inappropriate touch, and intersectional microaggressions for the combination of ableism, misogyny and spiritual condescension. Microaggressions are ‘subtle, stunning, often automatic, and nonverbal exchanges which are ‘put downs’’ (Pierce et al. 1978, 66). They are ‘brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to certain individuals because of their group membership’ (Sue 2010, xvi). The teachers in Gill’s story have shamed her body for both her yoga asana ‘ability’ and the symptoms of her chronic illness, and layered other ‘denigrating messages’ onto her.

Body activist Hanne Brown (quoted in Taylor 2018:9) says ‘There is no wrong way to have a body’. Despite receiving messages and behaviours which contradict Brown’s view, Gill has been inspired by her received abuse to become the yoga teacher that she did not experience. She is beginning to break down the systems of oppression through her resistance to them (Taylor 2018:46).

Case Study 2: Lucy

Lucy has felt Othered by being a fat, homosexual woman:

Question 8: During your history of practice, can you describe any negative experience(s) you may have had: physical/verbal/sexual abuse, any experiences of classes or teachers who made you feel in some way 'less than', e.g. too old, too large, or in some way not 'a fit'? If so, how did you act in response?

‘[A]s a teacher I have had that [negative] experience from both potential employers, refusing to even have my CV taken by gyms and studios because of my size/appearance. Also had students walk out because I didn't fit their image of how a yoga teacher should look. I have always felt other. I frequently feel disenfranchised for my size and have had many occasions where modifications for it aren't given. I also don't fit in the yoga world as a Queer woman and there is little to no representation of that. Fat and queer do not a yoga teacher make... but of course they do! But generally I just avoid the teachers and classes and studios I don't feel comfortable in, which is why I've practiced using online studios since 2009!‘

Question 9: What are your observations of how (if at all) the practice of yoga is changing with the pandemic? Do you think that teaching and practising yoga online makes the kinds of experiences described in question 8 more or less likely?

‘[This is] why I have practiced online for so long. It's more comfortable when you don't fit. I'm not sure if it will make a lasting change - I hope so. It's one of the main focuses of my work.’

Lucy tells of both the experience of microaggression, and the felt sense of being Othered, in response to both their body shape and their sexuality. They have chosen to teach in online spaces long before it was a necessity of the pandemic, because they feel more of a fit there.

Lucy expresses the wish to create lasting change, in response to the normative heterosexual hegemony. They are using their ‘experience as education’ to take a counter-hegemonic stance (Johnson 2017:79-81; Dewey 1897:77). The recommendation from social activists is that critical resistance strategies should act in collusion with other disempowered groups so as not to lose power (Creswell 1991:1297; Butler 2011: 167).

Discussion

1. Predictions for post pandemic yoga practice

How did the survey respondents envisage that yoga practice would look post pandemic? Most anticipated that the shift online during the pandemic would continue to open up wider opportunities for practice, with much more adoption of online practice in the comfort and safety of the home environment; this would probably be more welcoming for beginners, and result in a reduction in concerns of peer judgement or comparing self to others. Clearly there is no need for travel time or expense for online practice. During lockdown, there were reported reductions in body shaming, and decreased focus on practitioners’ yoga wear, with the resulting increase in perceived inclusivity. The increasing number of body positive teachers was offering more diverse and inclusive practice role models.

The disadvantages of online practice when people have a choice are perceived to be fivefold:

If practitioners leave their videos on, this can still feel intimidating, for reasons discussed in the ‘Pandemic Yoga Practice’ section. There is potential persistence of the glorification of the appearance of asana.

Accessibility to the internet is key. If a practitioner has no access to the internet, online practice is not a choice.

Online teaching has restricted pedagogic support, which could discourage beginners, and has potential concerns of safety of practice.

It becomes hard to separate yoga practice from practitioners’ ‘normal’ life, meaning that it could be hard to concentrate on practice.

Sustained online practice alone can feel isolating and impersonal.

During the data gathering period during late summer 2020, one respondent expressed certainty that ‘yoga will return to as it was soon‘; another was not so sure, saying ‘I don't know that these changes will last once we return to a studio environment. ‘ As the lockdown eased however, some teachers observed that class numbers dropped significantly. This was for four potential reasons:

Students were returning to work and had less time for practice.

People generally had less money overall due to challenges with income and job losses over the lockdown.

Teachers were observing a level of demotivation, boredom and ‘screen fatigue’ among students.

Opening up of social venues meant that students were being attracted to other ‘in real life’ activities.

One respondent described challenges for yoga studio owners who were having to reassess how they may or may not return to offering in-person group classes, including use of masks, limiting numbers of participants to facilitate continued social distancing, and eliminating pranayama and physical adjustments from the practice for safety reasons. By contrast, self employed yoga teachers were enjoying greater independence, after the initial ‘panic’ (Rice 2021) caused by lockdown restrictions, having found ways to have a more sustainable lifestyle and income online, away from dependence on studios.

In late 2020, the world was beginning to see a mixture of both studio and online teaching that was likely to persist into the near future, at least. At the time of writing (September 2021), the world has moved a little further. In early Sept 2021 The New York Times reported that we may be reaching the end of the COVID-19 Delta variant (Weber 2021b). Life has changed and for many that change has been both dramatic and traumatic.

A recent McKinsey workplace survey has revealed that, while employers are hungry for employees to be back in the office, and to return to a normality close to that before the pandemic, employees want a different, more flexible model (Figure 14) (DeSmet et al. 2021).

Figure 14: In office working days reported before pandemic and expected after pandemic (De Smet et al. 2021:2)

A review of current status of practice and teaching with online yoga teacher discussion groups in June and July 2021 revealed that the situation had potentially become even less clear. One teacher reported students anxious and resistant to return to in person teaching:

‘Students are making excuses not to come back to classes. Habituated fear/tension manifesting, as predicted a year ago. It only surfaces now, when people consider NOT wearing a mask, or returning to normal living and going to work etc. A veritable wall of excuses, reasons, whatever you want to call them, falls out when you open the cupboard door. They are apparently using free choice, but it's a decision grounded in underlying terror. As a therapist this horrifies me, it will take generations to dissipate.’

A second teacher described the destabilizing process of potential infection and self isolation caused by the post-lockdown quarantine regulations.

‘Well, it's been a weird week. I was happily teaching in person when I had to self isolate, so I'm back on Zoom. Not me. I'm still negative. I'm a week in - with extra time added on for bad behaviour (ok a second case.... everyone is well.... just like a cold)...Meanwhile I'm home perfectly well. Still negative watching life pass my window. A student yesterday pointed out that if I turned positive, they self isolate. Then we return and one turns positive and we all self isolate... ad infinitum. That's not sustainable.’

As in the workplace, a picture is emerging of a future that is likely to be a hybrid of online and in- person yoga practice, but with the scales tipping towards online for the short term, at least.

2. The traumatic legacy of the pandemic

As with other data I have examined relating to the pandemic, the message around its trauma impact is not straightforward. Many employees report that working from home through the stress of the pandemic has driven ‘fatigue, difficulty in disconnecting from work, deterioration of their social networks, and weakening of their sense of belonging’ (De Smet et al. 2021:2). While the pandemic is killing people, damaging the health of populations and challenging their health care systems, evidence is also emerging of its traumatic legacy (Weber 2021b; Kira et al. 2021).

The pandemic saw rises in anxiety, sleeplessness, panic attack and symptoms of depression and maladjustment (Kulkarni et al. 2021), as evidenced by these responses:

‘As a yoga teacher I have seen my students' needs change during the pandemic. We've done a lot more restorative asanas and gentle pranayamas. There's fear, uncertainty, loss, grief, exhaustion, anxiety, and the practice at this time has been to support them in finding safe spaces in the present moment, even during the chaos. Students have said that the online yoga has been the only thing keeping them together and supporting their mental health during this time.’ - Lisa

‘Yoga has changed during the pandemic. Online classes are a lifeline.’

Yoga practitioners (who are fortunate enough to avoid microaggressions) feel the benefits of their practices; the study showed that many were drawn to yoga initially for reasons of fitness or physical body ‘improvement’, but most return to practice habitually having experienced the less physical benefits of peace, wellbeing and mental hygiene.

A traumatic event is an overwhelming experience which incapacitates our normal mechanisms for coping and self-protection; trauma leaves traces on our minds and emotions, on our capacity for joy and intimacy, and even on our biology and immune systems (Van der Kolk 2015:1). The pandemic is layering traumas on our stressed systems that could take generations to dissipate, as epigenetics tells us that we inherit trauma in our DNA (ibid: 152). Fortunately, there is emerging evidence of just how much a lifeline yoga provides. The yogic toolkit of practices is helping navigate the uncertainty and stress of the pandemic; yoga practitioners exhibit less anxiety, stress, and fear, and relatively better mental health than those not practicing yoga (Nagarathna et al. 2021:1). Yoga and meditation practice may be an important adjunctive treatment for COVID-19 because of their immune boosting potential (Bushell et al 2020); the International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) is working on an initiative to support yoga therapists who are helping people with long COVID (Weber 2021b).

The subject of trauma returns me full circle to that of microaggressions in yoga. There is a paradox here: yoga provides a toolkit for creating the social resilience that we need to survive day-to-day microaggressions, and yet can also be the source of microaggressions. I have concluded from this study that the risk of receiving microaggressions is lower when practicing online; but herein lies yet another of the many paradoxes of yoga: in person gatherings heal trauma. Social support is the most powerful protection against becoming overwhelmed by stress and trauma (Van der Kolk 2015:79; Van der Kolk et al. 2014:1). We are missing this. Online yoga cannot give us this.

I had stated previously (see section ‘The impact of online teaching on abuse and body shaming’) that hypothesis 2 was proven at a superficial level. This consideration of trauma provides a more nuanced insight however. The hypothesis can only be said to be partially proven at best.

3. Intersectionality Conclusions

I return to the question of how to reform the yoga industrial complex, informed by the stories of the intersectional bodies of Lucy and Gill. Bodies are the sole unifying element of the human experience. The voices of Lucy and Gill, and the other stories in the ‘Intersectionality’ section, tell of experiences of misogyny, racism, ableism, fatphobia and homophobia in the context of yoga; these ‘isms’ and phobias are systems of oppression that make it hard to live in those bodies (Taylor 2018:4). The less ‘normal’ a person’s identity, the more ‘abjected’ their bodies and the more ‘fraught the waters of shame’ that they navigate. Butler calls this occupation of an abject body, ’arguing with the real’; an abject body is an unsafe place to live. (Taylor 2018: 30; Butler 2011 vii, 139)

Despite these embodied experiences, Lucy and Gill are modelling activism and change, by becoming yoga teachers who are better than those they had experienced. We learn to become who we are through interaction of our bodies with those of others, even (and perhaps especially) those who abuse. Merleau-Ponty (1945) calls this ‘mutual embeddedness’: we are part of one another on a body-to-body relational field.

What do these voices tell us about post-pandemic yoga? Intersectionality provides the means for dealing with groups of marginalizations. If we consider that all these practitioners’ identities intersect with that of ‘yoga practitioner’, the coalition of their identities serves as a basis to critique yoga as an institution. We can bring attention to how the identity of ‘yogi’ has been centred on the intersectional identities of a few ‘normative’ bodies. Through an awareness of intersectionality, we can better acknowledge the differences among us and negotiate how these differences will find expression within the group politics. Intersectionality attempts to reveal the processes of subordination, which the voices in the ‘Intersectionality’ section recount, and the various ways those processes are experienced by people who are subordinated and those who are privileged by them (Creswell 1991:1296-9).

Expressed simply, Lucy and Gill learned to be inspirational yoga teachers through their ‘mutual embeddedness’, their embodied experiences of microaggression. That is not to say that we should perpetuate these experiences. Changing an organization (in this case the yoga industrial complex) demands we act both radically and intersectionally; systems of oppression stand or fail based on whether we as humans uphold or resist them (Taylor 2018: 9,46). Lucy and Gill are modelling at the micro, human level, how to enact the required change in the yoga industrial complex.

4. Yoga is a practice of attention

How can we therefore create systemic change in the yoga industrial complex? Throughout its history, yoga has continually reinvented itself to find greater contemporary relevance. In searching for the method of transformation, I find that a chorus of voices are pointing towards some yogic advice: we must pay attention.

‘Noticing the world differently can have material consequences that could be the difference between taking care and perpetuating paradigms of oppression and needless suffering. ‘ (Akomolafe 2020)

We must pay attention to both the creative as well as the destructive potential of our body images; this is the critical step in the process of inventing new meanings, which are required and can lead to lasting systemic change. These changes can take hold if we realize that changing our relations to others is always an embodied process; we are connected to each other, and are mutually embedded. (Weiss 1998:170; Merleau-Ponty 1945).

Moving from body shame is a road of inquiry and insight; how we honour and value our own bodies impacts how we reciprocate that to others. This study highlighted the evidence of body shaming; we must prioritise the way that yoga treats bodies and body differences (Taylor 2018: 4-7). Butler insists that a body is defined by its vulnerability, not temporarily affected by it (Hedva 2016:9), and so the yoga industrial complex must align around the essential vulnerability of bodies, and its inclusivity of them, rather than its othering.

I recall the excellent answer from one survey respondent: the only thing that will change behaviour within yoga spaces is for teachers to receive mandatory and in-depth subconscious bias and anti- discrimination training, and empowering more future teachers from minority backgrounds. One simple way teachers can all begin to move this dial is to pay attention to language: ‘Fat’ (like ‘Black’) is a fact, not a term of abuse. Teachers’ language should cultivate body safety and lack of judgement (Karnes 2017). Johnson (2017) suggests that we must look at inequitable, damaging organisations, and enhance our laws to prevent discrimination.

Considering the recommendations of Karnes (2017) and Johnson (2017), I consider a practical example of changes that can be made within the yoga industrial complex. Turning this same attention to the survey response of a curvy yogi:

‘I am curvy and suffer from body image dysmorphia so am particularly vulnerable to feeling out of place in classes where the physicality and intensity of yoga is held as tantamount - e.g. hot yoga studios that pitch yoga as a weight loss tool. Some studios passively encourage fasts and juicing as a way of achieving the "optimal healthy body". In conversations at the studio, members and staff talk about how they are trying to lose weight and comments that "it would do you the world of good" have been made.’

If a yoga practice space or teacher is to ‘prioritise body differences’ or align around bodies’ vulnerabilities (Taylor 2018: 4-7; Hedva 2016:9), enhancing connection and ‘mutual embedding’, then the enrollment process could sensitively request knowledge of any topics which may be triggering for this yogi (for example body dysmorphia). Language guidelines for the space (or better still, for the entire yoga industrial complex) could preclude the encouragement of weightloss and fasts.

A draft program of changes can even be drawn up, responding to each of the experiential examples received in the survey, as an open letter to the yoga community.

5. “Transform yourself to transform the World”

(Grace Lee Boggs, quoted in brown (sic.) 2017 Introduction)

In these strange, traumatic times, the more I find I search for methods to speak to the intersectional voices of Lucy and Gill in the yoga community, the more I am finding advice to heal society itself. Karnes (2020) urges us again to pay attention:

‘Notice this. [T]his pandemic forces us to see now how arbitrary and cruel a capitalist society is. We have always had capacity to do these things, care for these people, but we don’t. [..] Mother Nature has called our bluff.’

We are mutually embedded with all in society. Hedva (2016:13) urges us to anti-capitalist protest through the radical action of care for ourselves and each other; support, honour, empower and protect each other, creating a new ‘politics of care.’

Is it really that simple, the process of societal transformation? brown (sic.) (2017:112) provides the rallying call for us to ‘become the systems we need’: we have to remember how to care for each other, which will take time, commitment and ‘a willingness to step outside of the comfort of the current and lean into the unknown, together.‘ We need to take back our bodies from patriarchy. We need to model caring for each other in the yoga world and ripple that out to society.

I return to the paradoxes highlighted by this study, the first of these being that yoga provides the toolkit for creating the social resilience that we need to survive day-to-day trauma from microaggressions, while the yoga industrial complex is the source of those microaggressions. The second of the paradoxes highlighted by this study is that the risk of receiving microaggressions is higher when practicing in person, but that in person gatherings hold the potential to heal trauma. This is not the first time yoga could been viewed as paradoxical: Strauss describes how yoga offers the potential to transcend such dichotomies (2002:248). To close here I offer a third paradox: yoga here is both shining a light on problems of trauma, microagression and body shaming, and offering us the cure.

Conclusion

The first hypothesis of the study was supported; results showed that primarily female, but also male, practitioners have experienced body-shaming, traumatic microaggressions in yoga spaces, and have also expressed feelings of body shame. In some cases this resulted from receiving abusive behaviour; in others it arose from feeling othered by the modelling of ‘yogic’ bodies in yoga spaces. These experiences were reported across a broad spectrum of MPY practices. They were more prevalent in the more ‘active’ practice types. Restorative and yin styles showed less instances; the reason is assumed to be that these practices are focussed less on activity and physical appearance, and more on the inner experience and process.

Opinions of online yoga practice are mixed, some enjoying the wider choice of practices, ability to practice at home, and greater agency and privacy, reducing (but not completely eradicating) the possibility of body shaming, and increasing feelings of safety. Some have continued to experience microaggressions; others express concerns around the image focus of online yoga. Many miss the community energy and level of pedagogical support possible online. Conversely however, having the ability to switch cameras off for online practice may actually facilitate a transition to a more internal, contemplative yoga practice. As we emerge from the pandemic, people are evaluating how to live more sustainably, adopting hybrid ways of working that combine home and workplace more than before. Yoga practice is likely to follow suit, with practitioners participating in both online and in person classes, with potential for both harm and healing in each medium.

Yoga has been described as a lifeline during the pandemic, not only creating online community to remediate the loneliness of lockdown, but also providing practices that are therapeutic for both the anxiety of the pandemic and for the physical symptoms of the virus itself. Studies are showing that the experience of both the illness and the social environment of the pandemic have been traumatic; yoga also provides a toolkit of practices which can offer relief for the experiences of trauma.

Yoga has often been paradoxical through its history and this study has highlighted another yogic paradox: that of being both a toolkit for trauma relief, but also, in the case of modern yoga and body shaming micro aggressions, the cause of the trauma.

If yoga is a microcosm reflecting the macrocosm of society, what can be done to heal yoga, and in doing so, can we heal society? Yoga’s othering is intersectional, as the case studies showed. The yoga community must address these issues intersectionally. Similarly, society must address its issues of division intersectionally. To heal society, we are invited to initially heal ourselves from oppressional trauma, by engaging in practices of the self that cultivate joyful somatic movement, resilience, community, grace and liberation (Taylor 2018:114; brown 2017:126, 203-5).

These recommendations sound very much like yoga practices to me.

Bibliography

Akomolafe, Bayo (2020) I, Coronavirus. Mother. Monster. Activist. https://www.bayoakomolafe.net/post/i-coronavirus-mother-monster-activist

Askegaard, S and Eckhardt, G. M. (2012) ‘Glocal yoga: Re-appropriation in the Indian consumptionscape’, Marketing Theory 12; 1; pp. 45-60.

Bevilacqua, D. (2017) ‘Are women entitled to become ascetics? An historical and ethnographic glimpse on female asceticism in Hindu religions’, Kervan - International Journal of Afro-Asian Studies, Vol. 21, 51-79.

Bondy, Dianne (2014) ‘Confessions of a Fat, Black Yoga Teacher.’ Yoga and Body Image: 25 Personal Stories About Beauty, Bravery, and Loving Your Body, Eds. Melanie Klein and Anna Guest-Jelley, 73- 82. Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications.

Bordo, Susan (1993) Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. Berkeley: University of California Press.

brown, adrienne maree (2017) Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, AK Press.

brown, adrienne maree (2019) Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, AK Press.

Bushell, W., Castle, R., Williams, M. A., Brouwer, K. C., Tanzi, R. E., Chopra, D. and Mills, P.J. (2020) ‘Meditation and Yoga Practices as Potential Adjunctive Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and COVID-19: A Brief Overview of Key Subjects’, The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, Jul 2020, 547- 556. http://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2020.0177

Butler, Judith (2011) Bodies that matter, Routledge.

Cartwright, T., Mason, H., Porter, A., & Pilkington, K. (2020). ‘Yoga practice in the UK: a cross- sectional survey of motivation, health benefits and behaviours’, BMJ open, 10(1), e031848. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031848.

Crenshaw, K. (1991) ‘Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color’, Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241-1299.

Cushman, A. and Jones, J. (1999 [1998]) From Here to Nirvana, Rider Books, London.

De Michelis, E. (2007) ‘A Preliminary Survey of Modern Yoga Studies’, Asian Medicine, 3(1), 1–19.

De Michelis, Elizabeth (2005) A History of Modern Yoga: Patanjali and Western Esotericism, Contiuum.

De Smet, A., Dowling, B., Mysore, M., Reich, A. (2021) ‘It’s time for leaders to get real about hybrid’, McKinsey Quarterly https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/people-and-organizational-performance/our-insights/its-time-for-leaders-to-get-real-about-hybrid

Dewey, J. (1897) My pedagogic creed, School Journal, 3, 77-80.

Federici, Silvia (2003) Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation, New York: London: Autonomedia.

Ferdinand, Tracy (2017) ‘Black Girl Yoga’, Race and Yoga 2.1. Gendlin, E.T. (1982) Focusing, New York: Random House.

Gendlin, Eugene (1982) Focusing: How To Gain Direct Access To Your Body's Knowledge, Rider.

Guest-Jelley, Anna (2012) ‘Yep, I’m a Fat Yoga Teacher.’, Frugivore, http://frugivoremag.com/2012/10/yep-im-a-fat-yoga-teacher/

Gutin, I. (2018) ‘In BMI We Trust: Reframing the Body Mass Index as a Measure of Health’, Social theory & health : STH, 16(3), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-017-0055-0

Hall, Stuart (1997) “The Spectacle of the Other.” In Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon, 225 – 279. London: Sage.

Hedva, Johanna (2020[2016]) ‘Sick Woman Theory’, originally published in Mask, The Not Again Issue, 2016. http://johannahedva.com/SickWomanTheory_Hedva_2020.pdf

Link above broken. Personal copy of document: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/cp3143qezt91evnb90ffy/Hedva_Sick_Woman_Theory.pdf?rlkey=1vdpoepsz4i82rsja76b9td0i&dl=0

Heilbrunn, B. (2004) La performance, une nouvelle idéologie? Paris: La Découverte.

Hernani, M., Hernani, E. (2021) “Online Yoga as Public Health Support in the time of COVID-19 Pandemic”, International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, v. 21, n. 2, p. 331-337, doi: 10.52155/ijpsat.v21.2.1978.

hooks, bell (1992) Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Books.

lyengar, B.K.S. (1984 [1966]) Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. Unwin Paperbacks, London.

Jain, Andrea (2014) Selling Yoga: From Counterculture to Pop Culture, Oxford University Press.

Jackson, P. (2002) ‘Commercial cultures: Transcending the cultural and the economic’, Progress in Human Geography, 26(1), pp. 3–18. doi: 10.1191/0309132502ph254xx.

Johnson, Rae (2017) Embodied Social Justice, Routledge.

Karnes, Amber (2017) ‘Making Yoga More Inclusive: Language Do’s and Don’ts for Teachers, was at Body Positive Blog, now at: https://yogainternational.com/article/view/inclusive-yoga

Karnes, Amber (2020) ‘Immunity’, social media post on 17 March 2020

Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H., Ashby, J. S., Elwakeel, S. A., Alhuwailah, A., Sous, M., Baali, S., Azdaou, C., Oliemat, E. M., & Jamil, H. J. (2021) ’ The Impact of COVID-19 Traumatic Stressors on Mental Health: Is COVID-19 a New Trauma Type.’ International journal of mental health and addiction, 1–20. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00577-0

Klein, Melanie, Guest-Jelley, Anna (ed.) (2014) Yoga and Body Image: 25 Personal Stories about Beauty, Bravery & Loving Your Body, Llewellyn.

Klein, Melanie (ed.) (2018) Yoga Rising - 30 Empowering Stories from Yoga Renegades for Every Body, Llewellyn.

Kulkarni M.S., Kakodkar P., Nesari T.M., Dubewar A.P. (2021) ‘Combating the psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic through yoga: Recommendation from an overview’, J Ayurveda Integr Med., Apr 12:S0975-9476(21)00059-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2021.04.003.

Mallinson J., and Singleton, M. (2017) Roots of Yoga, London: Penguin.

Maparyan, Layli (2012) The Womanist Idea doi: 10.4324/9780203135938

Mason, Heather (2020-2021) ‘Managing Coronavirus Anxiety With Yoga’, The Minded Institute Blog https://themindedinstitute.com/how-you-can-manage-coronavirus-anxiety-with-yoga/

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1945) Phenomology of Perception, London: Routledge.

Miller, Amara (2016) ‘Eating the Other Yogi: Kathryn Budig, the Yoga Industrial Complex, and the Appropriation of Body Positivity’ Race and Yoga 1.1 https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2t4362b9

Mrozik, Susanne (2006) ‘Materializations of Virtue: Buddhist Discourses on Bodies’ in Ellen T. Armour and Susan M. St. Ville, eds. Bodily Citations: Religion and Judith Butler. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 15-47.

Nagarathna, R., Akshay, A., Manjari, R., Vinod, S., Sai, S.M., Ravi, K., Judu, I., Sharma Manjunath N. K., Amit,S., Ramarao, N. H. (2021) ‘Yoga Practice Is Beneficial for Maintaining Healthy Lifestyle and Endurance Under Restrictions and Stress Imposed by Lockdown During COVID-19 Pandemic’, Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.613762

Newcombe, Suzanne (2013) ‘The Institutionalization of the Yoga Tradition: “Gurus” B. K. S. Iyengar and Yogini Sunita in Britain’, Gurus of Modern Yoga, 147–66. doi:10.1093/ACPROF:OSO/9780199938704.003.0008.

Orbach, Susie (2016) Fat is a Feminist Issue, Arrow.

Orbach, Susie (2018) ‘Forty Years Since Fat is a Feminist Issue’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jun/24/forty-years-since-fat-is-a-feminist-issue

Park, C., Braun, T. & Siegel, T. (2015) ‘Who practices yoga? A systematic review of demographic, health-related, and psychosocial factors associated with yoga practice’, Journal of behavioral medicine, 38 10,1007/s10865-015-9618-5.

Pierce, C.M., Carew, D., Pierce-Gonzales, J.V and Wills, D. (1978) ‘An experiment in racism: TV commercials’, In C. Pierce (ed.) Television and Education, 62-88, Beverley Hills, CA: Sage.

Ray, Sugata (2015) ‘The “Effeminate” Buddha, the Yogic Male Body, and the Ecologies of Art History in Colonial India’ Art History, 38: 5, pp. 916-939.

Rice, Annie (2021) ‘Close-ups, cats and clutter: what the online yoga teacher saw’, The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2021/feb/06/close-ups-cats-and-clutter-what-the-online-yoga-teacher-saw

Risman, Barrie (2021) ‘Yogis Reflect: How Has the Pandemic Changed Your Practice?’, Yoga International, https://yogainternational.com/article/view/yogis-reflect-how-has-the-pandemic- changed-your-practice

Schmaltzl, Crane Godreau, Payne (2014) 'Movement-Based Embodied Contemplative Practices: Definitions and Paradigms', Frontiers in Neuroscience, doi:10.3389fnhum.2014.00205

Sharma, Kanupriya, Anand, Akshay, and Kumar, Raj. (2020) ‘The Role of Yoga in Working from Home During the COVID-19 Global Lockdown’, Work, vol. 66, no. 4, pp. 731-737.

Singleton, Mark (2010) Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice, Oxford University Press.

Stanley, Jessamyn (2017) Every Body Yoga, Workman.

Strauss, S. (2002) ‘"Adapt, adjust, accommodate": The production of yoga in a transnational World’, History and Anthropology, 13:3, 231-251, doi: 10.1080/0275720022000025556

Strauss, S. (2005) Positioning Yoga: Balancing Acts across Cultures, New York: Berg.

Sue, D. W. (2010) Microaggressions in Every Day Life: Race, Gender and Sexual Orientation,Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Sullivan, Marlysa B., Erb, Matt, Schmalzl, Laura, Moonaz, Steffany, Noggle Taylor, Jessica, Porges, Stephen W. (2018) ‘Yoga Therapy and Polyvagal Theory: The Convergence of Traditional Wisdom and Contemporary Neuroscience for Self-Regulation and Resilience’, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, Vol 12 doi: 10.3389/FNHUM.2018.00067

Taylor, Sonya Renee (2018) The Body Is Not an Apology: The Power of Radical Self-Love, Berrett- Koehler.

Törzsök, J. (2014) ‘Women in Early Śākta Tantras: Dūtī, Yoginī and Sādhakī’, Cracow Indological Studies Tantric Traditions in Theory and Practice, Vol. XVI, pp. 339-367.

Tucker, Lindsay (2020), ‘How Loving Yourself Can Be a Revolutionary Act’, Yoga Journal, https://www.yogajournal.com/lifestyle/amber-karnes-on-how-loving-yourself-can-be-a-revolutionary-act/

Upadhyay, P, Narayanan, s., Khera, T.,Kelly,L., Mathur, P.A., Shanker, A., Novack, L. , Sadhasivam, S., Hoffman, K.A., Pérez-Robles, R., Subramaniam, B. (2021) “Perceived stress, resilience, well-being, and COVID 19 response in Isha yoga practitioners compared to matched controls: A research protocol”, Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications, Volume 22, doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2021.100788.

Van der Kolk, B., Stone, L., West, J., Rhodes, A., Emerson, D., Suvak, M., Spinazzola, J. (2014) ‘Yoga as an adjunctive treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial’, J Clin Psychiatry. 2014 Jun; 75(6):e559-65. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08561.

Van der Kolk, B. (2015) The Body Keeps the Score: Mind, Brain and Body in the Transformation of Trauma, Penguin.

Varman, R., Belk, R. W. (2009) ‘Nationalism and Ideology in an Anticonsumption Movement’, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 36, Issue 4, 686-700. doi:10.1086/600486

Weber, K. K. (2021a) ‘Dear Yoga Profession, Adapt or Die’, Subtle Yoga Blog, https://subtleyoga.com/dear-yoga-profession-adapt-or-die/

Weber, K. K. (2021b) ‘COVID Research and the Changing Yoga Profession’, Subtle Yoga Blog, https://subtleyoga.com/covid-research-and-the-changing-yoga-profession/

Weiss, Gail (1998) Body Images - Embodiment as Intercorporeality, Routledge.

Wineman, Steven (2003) Power Under - Trauma and Non-Violent Social Change, published online only http://www.traumaandnonviolence.com/files/Power_Under.pdf

Appendix: Body shaming anecdotal evidence from selected respondents

1 - Example responses from larger bodied practitioners

‘I am curvy and suffer from body image dysmorphia so am particularly vulnerable to feeling out of place in classes where the physicality and intensity of yoga is held as tantamount - e.g. hot yoga studios that pitch yoga as a weight loss tool. Some studios passively encourage fasts and juicing as a way of achieving the "optimal healthy body". In conversations at the studio, members and staff talk about how they are trying to lose weight and comments that "it would do you the world of good" have been made.’

‘I have found ashtanga practice particularly excluding as there is not space for me to jump through or back (e.g. thighs don't fit between arms, I can't lift my bum off the floor because my arms aren't long enough and my bum is "too fleshy").’

‘I have started feeling excluded from the yoga community at studios and now that I am a teacher I try to find work outside of studios so that I am not subjected to judgements (even if only implied) on my size. If I do attend classes by yoga teachers, I choose teachers whom I know are body inclusive and body positive advocates. At one of these classes, quite a physically demanding and challenging vinyasa flow with a lot of arm balances and strength postures, a student made the comment to me that "isn't it great that she is so brave and confident" and implying "because she has a larger body and still dares to teach". ‘

‘On a course in India which included ayurvedic talks I was singled out as Kapha which was described as negative because kaphas are seen as large and slow! There are other times when I've felt too large for yoga.’

‘My teacher training mentor commented on my weight (I was larger then) in almost every single conversation we had across 20 months - pinching/poking at my body when I attended her public classes while loudly proclaiming that I was too weak or soft in front of other students and constantly wanting to know what my diet consisted of. This behaviour was also extended to another student within my mentor group. We reported this behaviour to our course administration who had words with the teacher, ultimately making the situation worse for us as we were not allowed to change mentor. I had explained that I have a history of eating disorders and yet I was kept in this toxic situation. The other student ended up leaving the course while I stuck it out. It taught me a lot about how I wanted to treat my future students and the kind of teacher I strive to be for them.’

‘Told I didn't look like a yoga teacher as not skinny.’

‘I'm a big girl & I don't fit in the 'yoga image', but in all this time the only person who ever made me feel uncomfortable was my teacher trainer. She never verbalised what she felt but being a big person, I am used to the facial expressions of those who disapprove of me.’

‘I was told I would never do certain asana, I have been hit by a teacher, told I needed to lose my belly, some classes have not felt welcoming due to homogeneous skinny white bodies dominating.’

2 - Example responses from slimmer bodied practitioners

‘Frequently called out for being 'skinny' in a way that made me feel embarrassed. I used to suffer from an eating disorder and still hate attention being drawn to my body. I always freeze. It seems socially acceptable to pick on people because they are slim and it’s hard to know what to say in response. It's one of the reasons I rarely attend group classes nowadays. My ongoing recovery is more important to me than attending group classes.’

‘My teacher once said 'If you are strong, then do this' and I couldn't do the thing that she was asking us to do at the time, so I felt weak and this was not good for my self-esteem. Having a history of anorexia, I also feel quite triggered when teachers talk about 'burning' or 'sliming the waistline' etc. I definitely try to avoid doing so in my classes.’

‘Being told I was too skinny by many 'concerned' women’